How Lulu Built a Library

How Lulu Built a Library

By: David Heighway, Hamilton County Historian

For Women’s History Month, I thought I would look how women affected the growth of the area – even before they had actual political power. For most of the years that a library had existed in Noblesville, local women handled the responsibility of running it. When the time came for the library to have a building of its own, the women of the community were the ones who were instrumental in its creation.

Because of the natural gas boom, the year 1900 was a time of tremendous growth in Hamilton County. In an effort to make the Noblesville city library more accessible to the public and to provide proper housing for the collection, it was moved from a spare room on the Courthouse Square to the recently built high school building on Conner Street. A library fund was created, and in 1903, six hundred dollars’ worth of new books were bought.

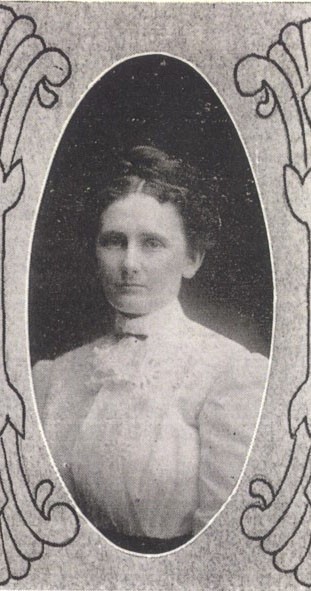

The size of the library, now containing hundreds of books, began to suggest a need for more professional administration. Librarians at this time, who were often young women, tended to only hold the position for a year or two. The situation changed in 1909 when a woman was appointed City Librarian who had not only been trained in the profession, but who also had a strong personality and a determination to make the library fulfill its role as a community institution. That woman was Lulu Miesse.

Miss Miesse was born in 1877 into a family of doctors. She began working in the school library while attending Noblesville High School and immediately after graduation began working in the separate city library, which was also at the high school. Miss Miesse got proficiency in the library sciences by attending Earlham College, Butler University and finally graduating from the library college at Chautauqua, New York.

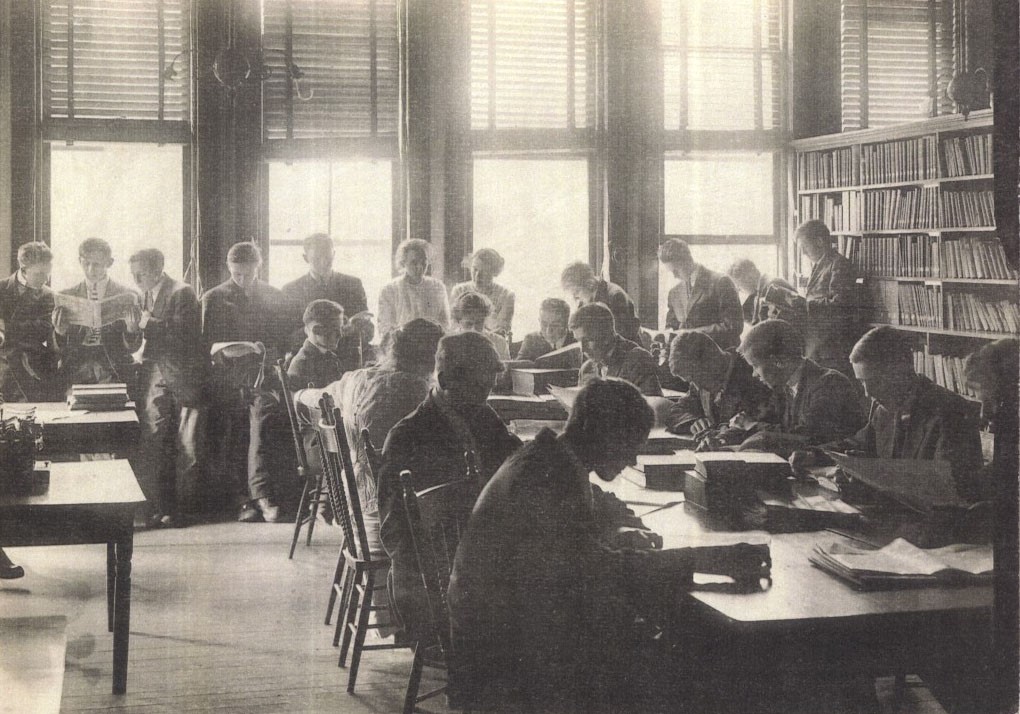

When she began work in Noblesville, one of her first actions was to properly catalog the books that had been accumulating since the first city library had been founded in 1854. The first catalog and acquisitions book, still at Hamilton East Public Library, shows that there were around 4000 books when Miss Miesse became librarian and that the collection was continuing to grow. After finishing this project, she recognized that her most serious need was space. With the growth of the population of Noblesville, school attendance had grown with it. At times, the library was so overcrowded as to be unusable.

When she began work in Noblesville, one of her first actions was to properly catalog the books that had been accumulating since the first city library had been founded in 1854. The first catalog and acquisitions book, still at Hamilton East Public Library, shows that there were around 4000 books when Miss Miesse became librarian and that the collection was continuing to grow. After finishing this project, she recognized that her most serious need was space. With the growth of the population of Noblesville, school attendance had grown with it. At times, the library was so overcrowded as to be unusable.

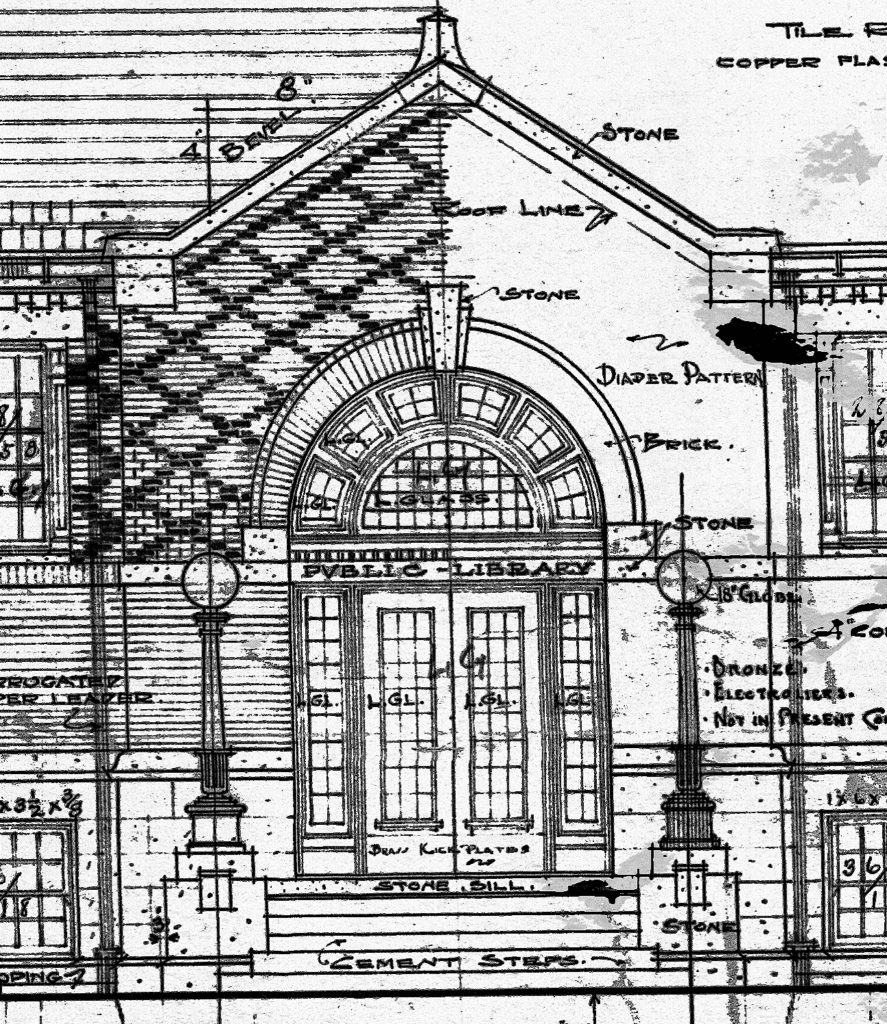

Fortunately, a solution was at hand. In 1893, the industrialist Andrew Carnegie had begun his program of endowing libraries in small communities. By the turn of the century, he was receiving five hundred to three thousand requests each day. His requirements were fairly straightforward. The community was to provide the building site along with funding for staff and upkeep, and Carnegie would give the money to construct the building. It seemed an easy enough project for Noblesville. Since the Ladies Aid Society provided the funding for support, the city had only to donate a plot of land. But getting this land turned out to be more difficult than Miss Miesse thought.

At the July 25, 1910, city council meeting, County School Superintendent John F. Haines presented a petition with several hundred signatures asking the council and mayor to appropriate money for the purchase of a site. The council promised to take action in a few weeks. However, months went by, and nothing was done. The reason for this, whether from a dislike of spending tax money or that it was simply considered unimportant, is unknown. The mayor and council members were considered to be a group of intelligent, civic-minded individuals. Finally, after waiting for six months for something to happen, Miss Miesse decided to take action.

In January of 1911, Miss Miesse invited several of the town’s leading women to a meeting at the school library. One participant referred to it as “a council of war”. Among the women who attended were Jennie Haines, the school superintendent’s wife, and Helen Thompson, who would later serve on the library board for 49 years. They decided to organize a mass meeting of all of the women’s social organizations in the community. These organizations were small, friendly groups usually meant for polite discussion and socializing. Miss Miesse turned them into an unexpected political force.

In January of 1911, Miss Miesse invited several of the town’s leading women to a meeting at the school library. One participant referred to it as “a council of war”. Among the women who attended were Jennie Haines, the school superintendent’s wife, and Helen Thompson, who would later serve on the library board for 49 years. They decided to organize a mass meeting of all of the women’s social organizations in the community. These organizations were small, friendly groups usually meant for polite discussion and socializing. Miss Miesse turned them into an unexpected political force.

The mass meeting was held on February 3, 1911, at the Hamilton County courthouse and an invitation was extended to every woman in the city of Noblesville. Between 200 and 300 women answered the call. Soon, there were too many people to fit in the small room that had been set aside for the meeting. Meade Vestal, the circuit court judge, (whose wife was in the group}, offered the use of the large main courtroom. Jennie Haines was asked to preside. She made the comment, “We suspected that we would get some kind of an answer in two weeks, but so far as I know, the Council has said nothing yet. We women feel that if the council really believed we were in earnest, they would act. I think that if we get the WHY big enough, we will get some kind of answer.” Lulu Miesse opened the meeting by telling the poor conditions of the library room, saying, “The conditions at the present library are such that the smaller children are crowded out by the larger ones”. Other women then gave a report on how other communities had built their libraries.

Then a representative from each club stood up and explained why their group supported the library. The Tourist Club, the Shakespeare Club, the Sappho Club, the Searchlight Club, and the Women’s Literary Club were a few of the groups represented. Prudence Craig said, “If we would be pure, we must have pure literature. If we would be virtuous, we must have virtuous literature, and not yellow back books. There is no better place for our minds to grow strong than in a Library. When boys reach a certain age, they want to go someplace besides home, and I am of the opinion that a general reading room would meet this requirement.” An African American woman named Ida Williams represented the Social Culture Club. She too said her group endorsed the library movement. All of this made banner headlines in the newspapers the next day.

After each group had spoken, a vote was taken to see who would attend the next city council meeting. It was asked that all women please stand that could attend. Almost everyone in the room rose to their feet. It was then suggested that the women attend with their husbands. This would have brought the total to nearly 600, far beyond the capacity of the council room, which was a small room on the second floor of the city firehouse. The women had planned to march to the council meeting as a single group, but in the end they only sent a delegation. However, the message had been sent by the women and understood by the officials. The city council met that week and voted to begin the process of getting a Carnegie library. On February 7th, the mayor wrote a letter to Andrew Carnegie and received preliminary approval. A plot of land at Tenth and Conner streets was purchased on June 3rd for $3,900. The library board, which still governs the library today, was organized on June 19th. In a note of profound irony, the building that was built is now part of the City Hall.